To be honest, I never really thought I’d have a shot like this in my portfolio. For a long, long time I had very little interest in shooting the full moon. It was too hard technically, too annoying, too difficult to make a good looking photo. At least that’s what I thought until I helped teach a PhotoPills / Milky Way photography seminar with Rafael from the PhotoPills team in July of 2017. His presentation of full moon shots opened my eyes to the beauty and possibilities of shooting Earth’s natural satellite. Not to mention the ex-engineer in me loved all the math and planning necessary to make it happen. So after the seminar was over I ordered a long lens for my camera (Nikon’s 200-500mm) and set about brainstorming ideas.

Where I live in Mammoth Lakes we are quite lucky to be near to some of most incredible geology in California. There is an ancient volcanic ridge that runs north-to-south just a few miles west of town. And over the eons that ridge has worn away into a series of sharp spires known as the Minarets. I knew these striking towers of rock would be the perfect backdrop for a full moon shot so I began the planning.

It’s not enough to simply look up the day of the full moon, arrive at the Minaret Vista parking lot on said date, and expect things to go off without a hitch. Because, you see, the moon moves around. A lot. From my perspective here in California the moon can change the location where it sets by around 6° per day. Meaning that if I am pointed directly at the full moon on day 1, the next day the moon could be 6° north or south of where my camera is looking. The moon’s position also varies with the sun: as the northern hemisphere heads into winter and the sun sets farther south every day the full moon actually appears farther and farther north. Meaning that the deepest parts of winter are when the full moon sets and rises farthest to the north. In the summer the full moon sets and rises far more southerly. In other words, depending on the day and season the full moon might not set anywhere near the Minarets! But if I change my own position I can affect the relative alignment of these key elements. The farther north I go personally the farther north I can make the moon apparently set. But how do I know exactly where to stand?

For me it begins by looking up the Minarets on Google Earth and knowing their exact position. Thanks to some topo map sleuthing and some personal experience I know that this is Clyde Minaret (the tallest one), and the rest scamper off to the north like this:

Now, it would be convenient to shoot this full moon photo from Minaret Vista because it’s an easy spot to get to. However, it would be an amazing coincidence if the geometry lined up perfectly that way. So in order to check the alignment I simply turned to PhotoPills to figure out where the next full moon (September at this point in the process) would set. And as it turned out, if I was standing at Minaret Vista on September 6th the full moon would appear to set far to the south of the Minarets.

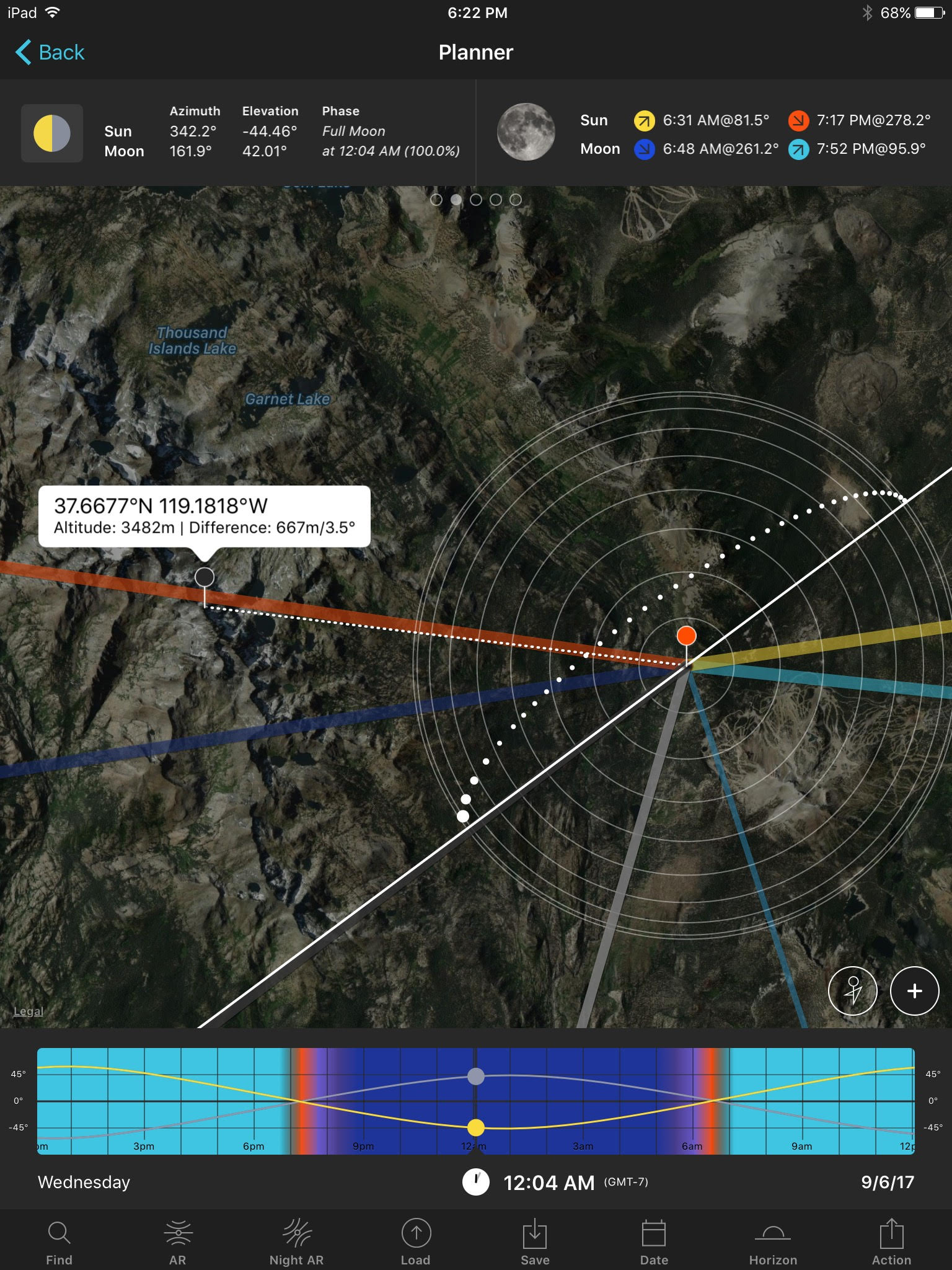

In this photo the red pin is my projected location, while the black pin shows the location of the Minarets. The deep blue line represents the direction of the moon set, which you can see is well south of where I’d like.

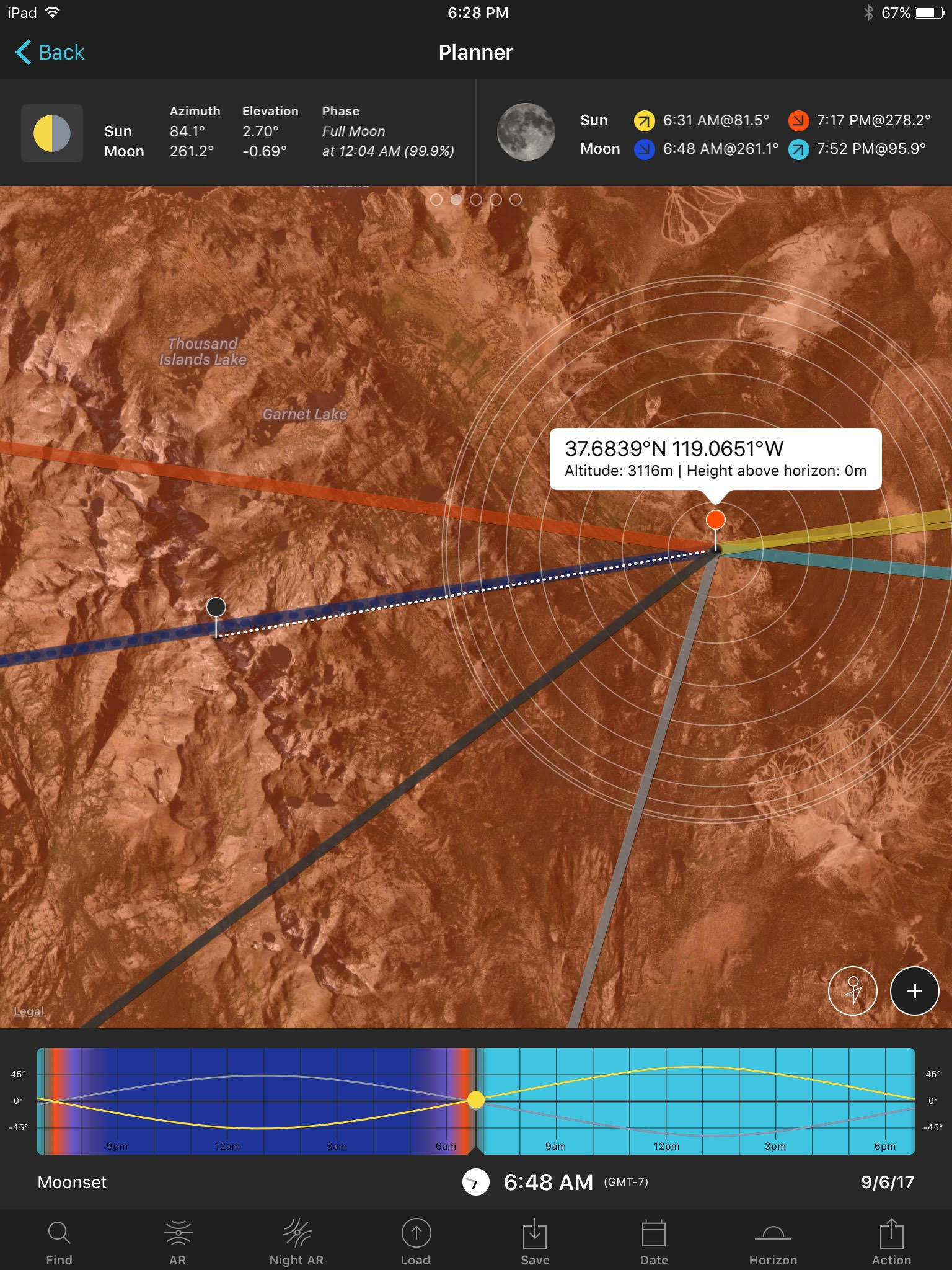

Which meant that I needed to shoot from a few miles north of Minaret Vista on that morning in order to actually see the full moon set over the Minarets. Within the PhotoPills app there are some very precise and cool ways to figure out exactly where I needed stand for the shot, but there’s also a quick and dirty way which is what I did: I simply moved my location pin by trial and error until the geometry showed the moon setting over the Minarets, like this in the photo below. I then saved that location as GPS coordinates I could punch into my phone.

From this location the moon will appear to set directly over the Minarets

Fast forward to the morning of the shoot. Moonset was slated for 6:48 am, but I guessed the moon would actually disappear behind the mountains 10-15 minutes before that. So I drove up the 4×4 road to my chosen location and arrived on scene around 6:10 am. I wanted time to double check my plan and verify in person that the moon was heading where I expected. I was pretty close right off the bat and some quick photos confirmed the moon would definitely drop right behind the Minarets.

Which meant at that point it was a matter of choosing my settings and trying a number of different compositions. Settings-wise I knew I wanted the moon to be large in the frame so I zoomed in to 500mm on my lens. Then I put my ISO to its lowest base setting of 64 and dialed my aperture to f/8. Because I was so far away from the Minarets (about 10.4 km) I knew they would be in the same focal plane as the moon, so I didn’t need any kind of extreme aperture like f/32. I then used my live view to zoom in and dial in perfect focus. Then it was time to pick a shutter speed, which is where things became a little more challenging than I had expected. There was a lot of smoky haze in the air from wildfires burning in the Sierra and that haze was eating up the ambient light. Which meant that at f/8 and ISO64 I needed a shutter of 1/30 sec to get a good exposure. 1/30 sec at 500mm is a recipe for blurry images so even though I was mounted on a tripod I turned on VR on the lens to get some extra stability. It helped a lot but in hindsight I’m wishing I had shot at something like ISO400 in order to get a shutter speed around 1/200 sec, which would have helped a bit with sharpness. However, in the moment the moon was moving so fast and I was scrambling to keep up, so changing my ISO and shutter speed didn’t click into the forefront of my brain. The other thing that was affecting sharpness was simply the gulf of air between me and the Minarets. Looking through the lens at 500mm I could easily see the air shimmering and shaking as temperature gradients caused the morning light to bend and quiver. Nothing I could do about those though so with those settings in place I rattled off a few images.

It was quite fascinating to see how far the moon moved laterally as it set. It seemed like it was almost on a 45° incline, and as it dropped lower in the sky it appeared to move an equal distance to the north. It began to approach the obvious low notch in the Minaret ridgeline but I could see it wouldn’t quite be positioned perfectly in the slot. So I scooped up my tripod and lens and sprinted northward through the pumice to get in position. As the moon sank toward the slot I fine tuned my location as well: 20 feet to the north. No, too far, back 10 feet to the south. Perfect. The moon is dropping into the notch and shoot shoot shoot! (At this point the ambient light had grown brighter as well and I was up to 1/80 sec on my shutter speed).

There is very little time for adjustment in a situation like that and in a mere 40 seconds the moon had moved from one side of the notch to the other.

However, right in the middle, exactly 20 seconds between those two shots the moon was in the perfect position and I was able to take home this photo, my favorite from the entire morning. And perhaps it’s not as razor sharp as it could be, but thanks to the smoke in the air the light had a beautiful quality and color that will be impossible to replicate in any future attempts. So as far as I’m concerned, it’s a keeper!

Any questions or comments about how this shot came to be? Let me know in the comments.

Joshua Cripps is a renowned landscape photographer who has garnered worldwide acclaim for his breathtaking images of our planet’s wild places. His photos have been published by the likes of National Geographic, NASA, CNN, BBC, and Nikon Global.

The Mt. Whitney Gallery was founded in 2023 by Joshua Cripps as a way to share his passion stunning landscapes of the Sierra Nevada and beyond.

Set at the foot of the breathtaking Sierra with a view of the range’s highest peaks, the gallery features large format, museum-caliber fine art prints of Josh’s signature photographs.

Course Login | Results Disclaimer | Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

© Copyright – Joshua Cripps Photography

24 Responses

makes me want to get a 200-500 mm lens. Great photos Josh!

I had the exact same reaction when I started seeing full moon shots.

Thanks, Anton!

Great writeup and perfect timing as we have a super moon coming the first week of December in the West according to PhotoPills. Have been planning out my shot and your comments on ISO and Aperture are helpful.

Excellent! Glad you found the article useful, James. Best of luck for the December moon!

Hi Josh:

Wonderful pictures (the silhouetted minarets are stunning!) and also super interesting blog post, thanks for sharing your experiences. It’s fascinating to realize how fast the moon is actually moving when trying to capture it! BTW: I love Photopills! What a great and super useful app, and in my view extremely useful. It replaced TPE for me for most part.

I love your work, thanks so much for posting this great content.

Sincerely,

Daniel

Well thank you so much, Daniel!! Yes, the moon is really hauling ass, especially when you just need two more seconds to line up the perfect composition. Whoosh, it’s gone!

Hi Josh, Thanks for an interesting article. Some people say you should switch off VR when using a tripod as it can make matters worse. I take it that is not your experience?

Alan, that is typically right for shooting from a tripod. However, that advice is typically used at much wider focal lengths or when your lens is perfectly steady. In this case being at 500mm meant even tiny jitters showed up through the lens. Putting VR on helped me minimize those movements.

Good stuff there Josh. The article has sparked some interest in incorporating the moon (possibly in partial phases also) into my night photography. Well done with the shoot and how you used photo pills to get the location you needed.

Cheers, Eric. Glad the article was stimulating! Best of luck to you in your future night and moon shoots.

Hey Josh – great article, and I love these images. Pretty amazing how the track of the moon varies, and how quickly it does so near the horizon. I’ve captured a few “super moon” images, but do need to extend my reach. I’ve been contemplating the 200-500mm Nikkor – what is your overall impression of this glass?

Keep up the most excellent work – I always look forward to more of your vids and newsletters. I know the podcast will also have their signature Cripps flair…

BTW – once an engineer, always an engineer – no “ex-engineer” allowed!!

No ex engineer allowed?? Haha! Ain’t that the truth. You can take the man out of engineering but you can’t take the engineering out of the man.

I’m pretty happy with the 200-500mm. I haven’t done a lot of technical tests on it yet but I’m very happy with the image quality. Obviously it’s going to be slower and not quite as sharp as a 500mm prime, nor is the focus going to be as fast, but it also costs $9,000 less. And for the price the performance is very solid. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it for high-speed sports or wildlife photography, but for doing something like shooting the moon or distant landscapes it’s a keeper.

Great moonshot narrative!

Except for setting the alarm and getting up and out way before dawn, moonset is easier than moonrise. The moon is already above the horizon and available for initial focus, exposure, etc. and you can see where it is and where its going. In addition to PhotoPills, I’ve found Photographer’s Ephemeris useful for moonshot planning (more so, actually). Its companion app Photo Transit is handy for experimenting with focal length and field of view choices.

Not satisfied with “Rule of 500” or “Rule of 600” for limiting star trailing (or moon motion in this case) I created a spreadsheet to calculate the actual drift rate across the sensor as a function of focal length and declination angle. On the morning of 6 Sept. the moon was at declination – 8.5 degrees. For a 300mm lens on a Nikon D750, for instance, the image drift rate would be about 3.6 pixels/second. At 1/30 sec or shorter exposure, if there was any softness in your images, it was due to factors other than the rotation of the earth, primarily the miles of atmosphere between you and the moon (not just between you and the Minarets).

Really stunning photographs resulted, and such good fortune to have such a spectacular horizon to play with in your neighborhood.

Excellent information here, Michael. Thanks for chiming in with this technical approach. And thanks so much for the kind words. I wish you much success with your own moon shots.

Great info to have. Will have to give it a try. Have you ever photographed the Northern Lights and how? Like camera settings and lens used.

I’ve only photographed them once and it was during a weak storm. So I had to use settings similar to shooting the Milky Way: wide aperture, high ISO, shutter speed around 6-15 sec.

Excellent. Thanks for the unexpected tutorial. I’ll be applying that info to the next full moon, and aim to create a shot near the horizon. Time to experiment!

Good luck to you!

Great to see your planning and your real-time adjustments to get this image. I’ve never really thought about getting a moon set. I’ve always concentrated on moon rises. Now I have a new challenge!

Yes! No matter what it’s a challenge. That sucker hauls!

Thanks for the description of how you got the shot. I like your final as well. Shooting the moon has always been a challenge for me. I’ve done most in “bulb” mode and manually timing my shots. I use the app LightTrac for sun/ moon rises and settings. Pretty handy. Thanks again. I enjoy your vids.

Thanks, Stephen. Shooting the moon is definitely a challenge. Without seeing your process it’s hard to say for sure but you might be doing yourself a disservice by shooting the moon in bulb mode. It’s incredible bright, and often requires shutter speeds of 1/250 sec or faster. Hard to do that in bulb.

Cheers,

Josh

Hi Josh, you wrote that you turned on the VR on the lenses. What stays VR for? I know only IS for Image Stabilizer. Thanks, Caterina

Hi Caterina,

VR is Vibration Reduction, which is Nikon’s analog of IS.

Cheers,

Josh